A bowl of corn pho captures the rustic flavors and mountain soul of northern Vietnam

In the highlands of northern Vietnam, food is not merely sustenance. It is a cultural language. Smoked meats, fermented pork of the Muong people, grilled stream fish, five-colored sticky rice, bamboo-tube rice, corn noodles, and dishes made from forest moss all reflect how ethnic communities have adapted to rugged terrain and seasonal rhythms over generations. Each recipe carries layers of indigenous knowledge - about climate, crops, preservation, and taste - refined over centuries.

For travelers, cuisine is often the most immediate and memorable gateway into a destination. Many visitors recall a place not by its landmarks, but by a dish they tasted beside a fire or a meal shared in a stilt house kitchen. “I miss that place because of one bowl of soup,” is a sentiment frequently heard among those returning from Vietnam’s highlands. To fall in love with a land, it seems, one often begins with its flavors.

Globally, culinary tourism is on the rise, accounting for a growing share of travel experiences. For mountainous provinces, traditional cuisine represents a rare asset - one that cities cannot replicate. Its value lies first in authenticity, then in its ability to generate livelihoods. Local dishes and ingredients can be transformed into branded products, specialty goods, or OCOP items, opening new markets while keeping value within the community.

Equally important is the experiential nature of food tourism. Visitors are no longer content to simply eat; they want to cook, listen, learn, and participate. When done responsibly, culinary tourism can be remarkably sustainable - preserving ecosystems, encouraging local sourcing, and reinforcing cultural pride rather than eroding it.

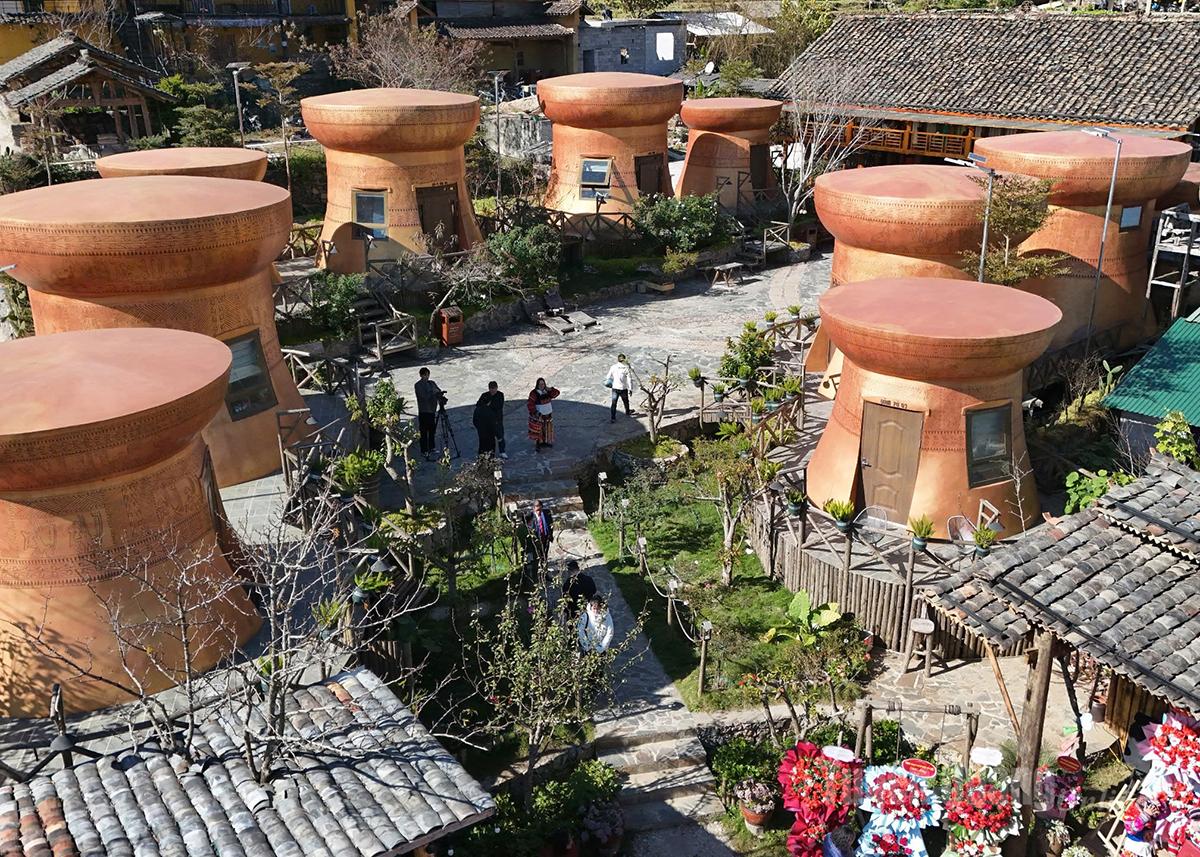

Success stories from northern Vietnam underscore this potential. Lao Cai has built recognition around sour noodle soups and traditional horse meat dishes; Ha Giang has drawn attention through buckwheat-based foods and corn pho; Tuyen Quang has carved its own niche with five-colored sticky rice, bamboo rice, and communal tray meals that embody the region’s spirit of sharing and simplicity. These are not fleeting trends, but long-term cultural assets.

“Com met”, food showcasing on a large, handwoven bamboo serving tray, reflects the communal spirit and rich flavors of Lam Binh’s mountain communities

Yet the rise of culinary tourism also brings risks. As demand grows, shortcuts appear. Recipes are simplified, ingredients substituted, and traditional methods abandoned in favor of speed and convenience. Some dishes are “urbanized” or overly adapted to external tastes, losing their original character. In other cases, cuisine is reduced to mass-produced souvenirs, stripped of context and meaning.

A more subtle challenge is generational. Younger people, drawn to fast food and modern lifestyles, may feel detached from traditional cooking. Without deliberate efforts to pass on knowledge, the chain of transmission can quietly break, leaving dishes to survive only in memory.

Addressing these challenges requires a coordinated approach. Indigenous culinary knowledge must be documented and digitized, alongside the stories and rituals connected to food. Clear standards should be established to protect authenticity and ingredient integrity. Local products should be developed in close connection with native resources, not detached from them.

Equally vital is education. Apprenticeship programs, community workshops, and intergenerational exchanges can reconnect young people with culinary heritage. Experiential tourism should be encouraged, allowing visitors not just to taste local food, but to understand and respect the culture behind it.

Food does more than nourish the body. It nourishes memory, identity, and belonging. For ethnically diverse, mountainous localities like Tuyen Quang, cuisine is a distinctive competitive advantage. When protected and thoughtfully developed, traditional food becomes more than cultural pride - it becomes a pillar of sustainable tourism, a bridge between people, and a compelling invitation to discover the soul of the highlands.

Nguyen Thanh Hieu

From a Vietnamese news on Tuyen Quang online